The NSWA tries to highlight unique and interesting places throughout the watershed. We recently sat down with a member of the Edmonton Native Plant Society (ENPS) to learn about a unique prairie-badland area on the north end of Gibbons.

Back in 2011, the Edmonton Native Plant Society (ENPS) was approached by a member of the Edmonton Cactus Society about a unique landscape on the north end of the Town of Gibbons. Some of the ENPS members visited the area and were delighted to find such a uniquely preserved ecosystem. A long-time member of the ENPS, Patsy Cotterill, describes her first visit to the area, saying, “The first time I saw the escarpment in the summer I was blown away by its resemblance to the badlands of the south, and wondered why I had driven by it so many times without stopping to look."

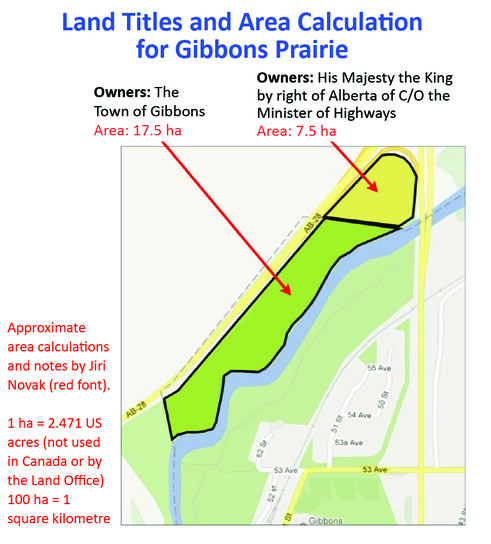

Approximate calculation of the region is 24 hectares. Courtesy of Google maps and Jiri Novak.

The escarpment occurs between the north side of the Sturgeon River and Highway 28. Part of the approximately 24.5 hectares of land is owned by the town and part is owned by the Crown, (as seen in the diagram above).

A UNIQUE GEOLOGICAL STORY

Geologist and author Dale Leckie explains that although the area falls within the parkland ecozone, after glaciers receded 14,000 years ago, “there were warm periods when vegetation dried out in places and sand dunes became active. I suspect that the prairie ecozone would have expanded northwards at this time. That would be the ideal time for the ‘badlands vegetation’ to move north. Subsequent periods of increased rain and cooling caused the parkland ecozone to expand further south, with 'badlands vegetation’ being now preserved in isolated localities along south-facing slopes, like that of the Sturgeon River at Gibbons.”

A view of the exposed sandstone and bentonitic clay at the north end of the escarpment. Photo credit: ENPS.

The Sturgeon has cut down through layers of sediment (formed in Cretaceous times, about 144-65 million years ago), to expose outcrops of bentonitic clay and sandstone. Surrounding these bare outcroppings are ‘badlands vegetation’ such as blue grama grass, prairie sagewort, and prickly pear cactus.

Escarpments such as these, with native grasses and prairie flora near Edmonton, are rare since European settlement, so they tend to be found along river valleys which are untouched by agricultural or residential development. Cotterill says, “It’s a little slice of badlands this far North. I know of one or two other badland occurrences, such as Kleskun Hills Provincial Park near Grand Prairie.”

Fossilized cones found in the Gibbons prairie-badlands escarpment area are associated with Cretaceous sediments. Photo credit: Patsy Cotterill.

The prairie slopes have “large, lichen-covered boulders and an extensive soil crust of lichens and small mosses. These form a “cryptogamic crust which stabilizes the soil and allows the growth of higher plants,” says Cotterill. This crust slows soil erosion and cannot be artificially restored once lost.

The south and southeast-facing exposures of these particular slopes mean more sun exposure and the rapid drainage of the slope, favours the growth of prairie species more often found in southern Alberta.

RARE & COMMON PLANTS IN THE AREA

To date, the ENPS has recorded 167 species there, including 29 grass species, which Coterill calls “absolutely brilliant”. She says that a similar nearby native prairie would only contain about a dozen grass species, so this region contains more than double that number.

When asked to name which plant species make the area unique, Cotterill begins with the grasses: “Needle-and-thread and porcupine grasses are very characteristic of the southern species.” She continues, “We have wonderful patches of sand grass, we have muhly grass, we have wheat grasses, blue grama grass, we have reedgrasses, which is from the Calamagrostis genus.”

A vista of blue grama grass, also known as eyelash grass. Photo credit: M. Parseyan

A couple of years ago, Cotterill says, “A visiting rare plant expert discovered the existence of two small populations of Canada ricegrass, which is considered a rare species”. Canada ricegrass falls under a S2 provincial designation, which means it only has 6-20 occurrences across the province.

Canada ricegrass is a rare find in Alberta, with only 6-20 occurrences. Photo credit: M. Parseyan.

Plains rough fescue has also been found in very small quantities. Cotterill notes that it “was the major grass of the Parkland and Mixedgrass Natural Regions supporting bison and later the ranching industry. So that is very good to see.”

Forbs (herbaceous flowering plants that are not grasses, sedges or rushes) include the fragile prickly pear cactus, which is the most northerly cactus in the world. There are also four species of milk-vetch, among which the two-grooved milk-vetch would normally be found east and south of Calgary, in the Mixedgrass Natural Subregion.

Fragile prickly pear (cactus) occupies the steeper, bare, badland slopes. Photo credit: Patsy Cotterill.

In terms of flowers most people would recognize, Cotterill begins with a couple of spring favourites: the prairie crocus and three-flowered avens. Avens’ dusty rose flowers and seedheads make pastures appear reddish, which is why they are also known as prairie smoke. The narrow-leaved meadowsweet shrub is also found there in the riparian area and is popular with pollinators. Cotterill notes that it mostly seems to occur east of Edmonton, but isn’t common west of the city.

Scarlet globe-mallow is typically found in prairie or badland ecosystems. Photo credit: Patsy Cotterill.

Cotterill explains, “This diversity is due to the fact that the escarpment includes several different habitats: the upper badland slopes, the lower, moister grassy slopes, the riparian fringe and the wooded ravines.“

Gardner’s saltbush, a typical badlands plant, was named for its ability to survive in highly saline areas. All badland plants show adaptations for survival in a dry, exposed environment. Photo credit: Patsy Cotterill.

VISION & THE PATH FORWARD

The ENPS are hoping to get the area more formally protected and advocate responsible recreation. There has been damage to vegetation in the area caused by OHVs and this precarious ecosystem cannot withstand too much compaction.

Wildflowers and native grasses in full bloom in the moist meadow at the bottom of the Gibbons prairie-badlands escarpment. Photo credit: ENPS.

The ENPS is making ongoing efforts to get local support to protect the area, including fencing, and organizing field trips. Cotterill believes the existing trail across the escarpment would need some improvement and possibly a guard rail to allow regular hiking and interpretive visits. Interpretation is very desirable because probably few people appreciate how special this grasslands site is. She adds, “Further, strong local support for its preservation would be invaluable."

FINAL THOUGHTS

Cotterill sums up her thoughts on the area, by saying, “Ecosystems like the badlands escarpment at Gibbons are living museums, providing a showcase into geological and natural histories of times past and illuminating the landscapes of today. We need to safeguard them.”

LEARN MORE:

Learn about the ENPS

Visit the ENPS Facebook page